Stay Updated with Everything about MDS

Thank you! Your submission has been received!

Oops! Something went wrong while submitting the form.

Chilat Doina

October 10, 2025

Let's cut right to the chase: Cost of Goods Sold (COGS) is simply the total direct cost you paid for the products you actually sold.

Think of it as the wholesale price tag on your inventory, from your perspective as the seller. Getting a solid grip on your COGS is the absolute first step to making smarter financial decisions that actually move the needle on growth.

Let’s say you sell custom-printed t-shirts online. Your COGS for a shirt you sold today would be the cost of the blank t-shirt itself, the ink used for the design, and maybe a small portion of the direct labor cost if you pay someone per shirt they print.

What it does not include are things like your website hosting fees, the salary of your customer service rep, or what you spent on that last Facebook ad campaign. Those are your operating expenses—a totally different bucket of costs.

COGS is laser-focused on the direct costs tied to producing or buying the items that have officially left your shelves. It's a snapshot of what you spent to create the things you successfully sold over a specific period.

This number isn't just some accounting formality you fill out once a year. It's one of the most vital health indicators for any business that sells physical products. Nailing your COGS calculation is non-negotiable because it directly shapes your entire financial picture.

In short, COGS tells the story of your production efficiency. It isolates the direct costs of your sales, giving you a crystal-clear view of how profitable your core products are before a single dollar of overhead is factored in.

When you truly understand what makes up your COGS, you gain immense control over your profitability. This knowledge empowers you to make smarter, more strategic moves in everything from inventory management to supplier negotiations.

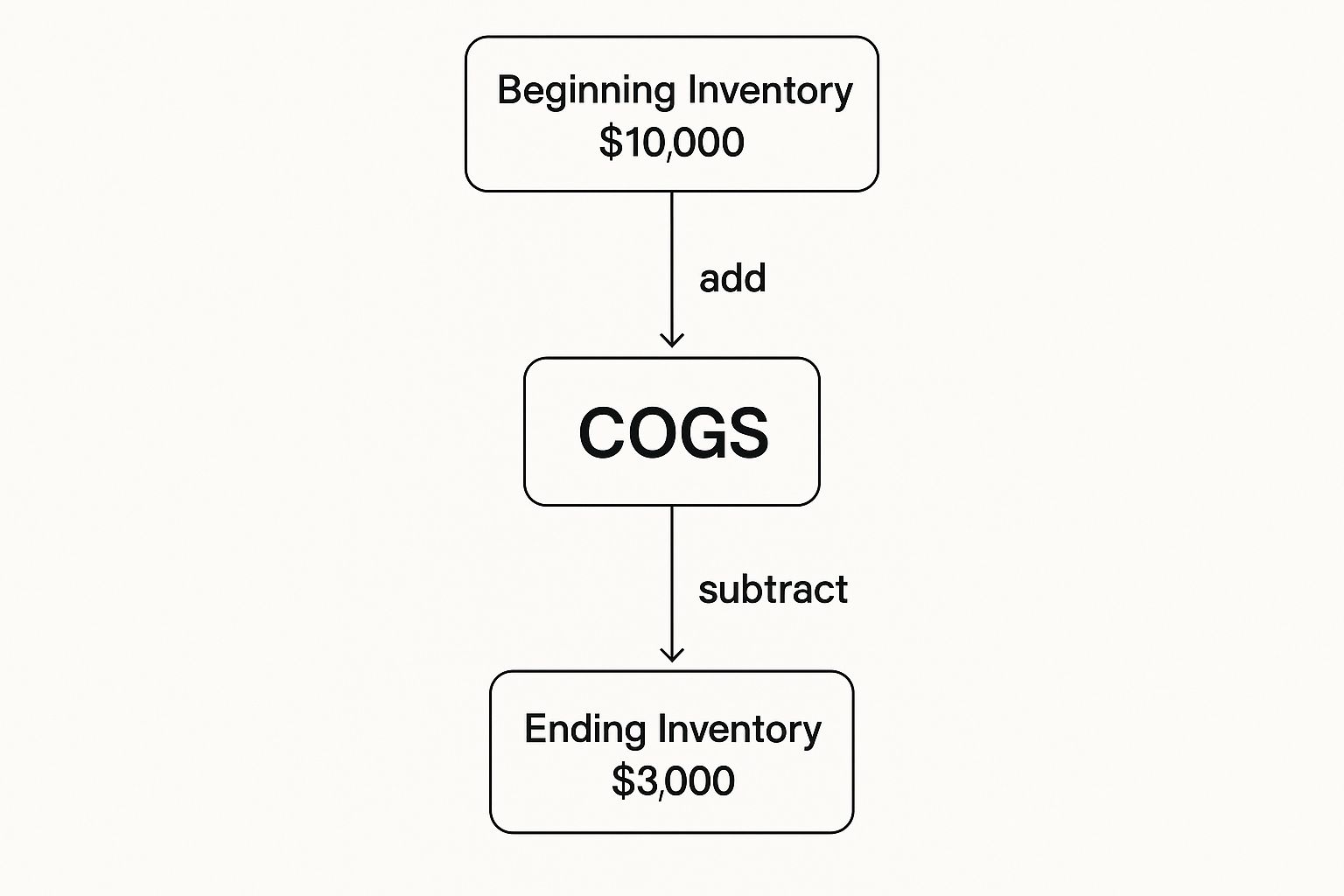

Alright, now that you’ve got a handle on what Cost of Goods Sold is all about, let's roll up our sleeves and get into the actual calculation. The good news? The formula is surprisingly simple and works for just about any business that sells physical products.

At its core, the COGS formula is just a logical way to track the value of your inventory as it moves over a set period—be it a month, a quarter, or a full year.

Think of it like this: you figure out what you started with, add what you bought, and then subtract whatever you have left over. What remains is the cost of the stuff that must have been sold.

The Universal COGS Formula:

Beginning Inventory + Purchases – Ending Inventory = Cost of Goods Sold (COGS)

This isn't just some handy tip; it's a fundamental piece of financial accounting. In the U.S., GAAP (Generally Accepted Accounting Principles) standards require this calculation. It's so critical that it sits right at the top of your income statement, just below revenue. Subtracting COGS from your revenue is what reveals your gross profit—the first and most important measure of your business's profitability.

If you're interested in the bigger picture, you can explore more about these financial management principles and see how COGS fits into your overall financial health.

To get an accurate COGS number, you need to nail down the three key variables in the equation. Each one tells a vital part of your inventory's story for the period.

When you plug these three numbers into the formula, you perfectly isolate the cost of only the products that left your possession because they were sold.

One of the most common hangups for sellers is figuring out what's a "direct cost" (part of COGS) versus an "indirect cost" (an operating expense). Getting this right is absolutely crucial, because mixing them up will throw off your numbers and give you a false sense of profitability.

To put it simply, direct costs are the expenses tied directly to creating the product itself. Indirect costs, often called overhead, are the expenses of running the business, but they aren't part of the physical product.

Here’s a quick-glance table to make it crystal clear.

Cost CategoryIncluded in COGS?ExampleRaw MaterialsYesThe fabric for your t-shirts, the wood for your furniture.Direct LaborYesWages for the factory workers who actually assemble the products.Shipping of SuppliesYesThe freight cost to get raw materials to your manufacturing facility.Marketing & AdsNoYour budget for social media campaigns or Google Ads.Rent & UtilitiesNoThe monthly rent for your office or warehouse space.Admin SalariesNoSalaries for your marketing manager or customer service team.

As you can see, the distinction is all about proximity to the product. If a cost is an essential ingredient in making the product, it’s COGS. If it’s a cost to run the business that sells the product, it’s an operating expense.

Knowing the formula is one thing, but seeing it work with real numbers is where it all starts to click. Let's shift from theory to practice with a couple of clear, step-by-step examples you’d actually see in an e-commerce business.

First up, a simple scenario for a clothing reseller buying finished goods. Then, we'll look at a handmade candle maker, which adds the small step of tracking raw materials.

Imagine you run an online boutique that sells vintage jackets. You buy them wholesale, so your direct costs are pretty straightforward—it's just what you pay for each finished jacket.

Let's calculate your COGS for the first quarter of the year.

Now, we just plug those numbers into the formula:

$10,000 (Beginning Inventory) + $5,000 (Purchases) – $3,000 (Ending Inventory) = $12,000 (COGS)

Your Cost of Goods Sold for that quarter was $12,000. That number isn't just a random figure; it represents the exact cost of only the jackets that your customers bought during that period.

This infographic breaks down how those three pieces fit together to find your COGS.

As you can see, the logic is simple. If you started with a certain amount and added more, the total value of goods you could have sold was $15,000. By subtracting what you still have ($3,000), you're left with the cost of what must have been sold.

Okay, let's switch gears to a business that makes its own products. This adds a tiny wrinkle, since you're tracking raw materials instead of finished goods. Let's say you're an artisanal candle maker. Your direct costs are things like wax, wicks, fragrance oils, and jars.

For this one, let's figure out COGS for the month of April.

We'll use the exact same formula:

$2,000 (Beginning Inventory) + $1,500 (Purchases) – $1,000 (Ending Inventory) = $2,500 (COGS)

Your COGS for April was $2,500. This figure represents the cost of all the raw materials that went into the specific candles you sold that month.

Nailing down your COGS is the first, most critical step to understanding your true profitability. Once you have this number, you can subtract it from your total sales to find your gross profit. If you want to take the next step, you can learn more about the profit margin calculation formula in our other guide. That's where you start to get a real, honest look at the financial health of your business.

Figuring out your Cost of Goods Sold seems simple enough at first. But then a tricky question pops up: what happens when you buy the same product at different prices over time? When you sell one, which cost do you use?

The answer to that question can completely change your COGS, your profit margins, and even how much you owe in taxes.

This is where inventory valuation methods come into play. They are the accounting rules you use to assign costs to your inventory, and the one you pick can paint a very different picture of your business's financial health. Let's break down the three main methods.

The First-In, First-Out (FIFO) method is probably the one that makes the most intuitive sense. It works exactly like it sounds: the first products you bring into your inventory (First-In) are considered the very first ones you sell (First-Out).

Think about how a grocery store stocks its milk. To keep things from spoiling, they always push the oldest cartons to the front of the shelf so they sell first. Your accounting under FIFO works the exact same way—the cost of your oldest stock is what gets assigned to COGS.

Next up is the Last-In, First-Out (LIFO) method, which is the complete opposite of FIFO. This approach assumes that the most recent products you bought (Last-In) are the first ones you sell (First-Out).

Picture a barrel of nails at a hardware store. Customers just grab what's on top, which is where the newest batch of nails was just dumped. The older nails just sit at the bottom, untouched. That’s the core idea behind LIFO.

The historical development of these accounting methods is directly linked to industrial progress. As businesses grew more complex, they needed better ways to match costs with sales. Adopting systems like FIFO and LIFO allowed them to manage fluctuating inventory costs more effectively. You can learn more about how these cost-flow assumptions evolved on meegle.com.

Finally, there's the Weighted Average Cost (WAC) method, which smooths out the peaks and valleys. Instead of obsessing over which specific batch an item came from, you calculate a single average cost for all identical units you have in stock.

To find this number, you simply take the total cost of all goods available for sale and divide it by the total number of units. Every time you make a sale, you use this blended average cost for your COGS calculation.

This method gives you a more stable and moderate financial picture, avoiding the sharp swings you can get with FIFO and LIFO. It's a fantastic middle-ground approach that also simplifies your bookkeeping.

Choosing the right valuation method is a huge part of mastering your inventory. If you're running into issues, check out our guide on overcoming common inventory management challenges for more strategies.

Calculating your Cost of Goods Sold is just step one. The real magic happens when you turn that number into a strategic tool to guide your business forward. By itself, a COGS figure is just a historical fact; when you start analyzing it, it becomes a powerful key performance indicator (KPI).

The best way to do this is by looking at your COGS as a percentage of revenue. This simple ratio cuts through the raw dollar amounts to reveal the true efficiency of your operation. It tells you exactly what percentage of every dollar earned is spent just to create the product you sold.

To find this vital metric, the formula is refreshingly simple:

(COGS / Total Revenue) x 100 = COGS Percentage

Let's say you pulled in $50,000 in revenue last quarter and your COGS was $20,000. Your COGS percentage would be 40%. This means that for every single dollar you made, 40 cents went directly toward the cost of the product itself.

Tracking this percentage over time is where you'll find the most valuable insights. A single snapshot is useful, but a trend tells a story about your business's financial health and where it’s headed.

A rising COGS percentage can be an early warning sign. It might mean your supplier costs are creeping up, your production process is getting less efficient, or maybe your pricing hasn't kept pace with inflation, which is now squeezing your profitability.

On the flip side, a falling COGS percentage is a fantastic signal. It could mean your bulk purchasing strategy is paying off, you’ve successfully negotiated better rates with vendors, or you’ve found smart ways to streamline production.

Comparing your COGS percentage to industry averages gives you crucial context. COGS varies wildly across different sectors. Manufacturing firms often see COGS between 60% and 75% of revenue because of high material and labor costs, while many retailers land somewhere around 70%. Service-based businesses, naturally, have much lower percentages.

Knowing where you stand helps you see how your efficiency stacks up against the competition and points you toward smarter cost management.

Ultimately, analyzing your COGS empowers you to ask the right questions:

Answering these questions transforms COGS from a simple accounting line item into a strategic compass for your business. It's also the critical first step in understanding your true profitability.

If you're ready to see how this all impacts your bottom line, our guide on what is gross margin is the perfect next read. And remember, beyond just crunching the numbers, understanding available small business tax concessions can further boost your profitability and sharpen your financial planning.

Figuring out your Cost of Goods Sold might seem straightforward on the surface, but tiny errors can create massive ripple effects. Get it wrong, and you're looking at skewed profit margins and, frankly, bad business decisions. Nailing this number is a non-negotiable, and that starts with dodging the most common pitfalls.

One of the biggest tripwires is mixing up direct costs with operating expenses. It’s an easy mistake to make—accidentally lumping in things like marketing spend, sales commissions, or your office rent. Just remember the golden rule: COGS is only for costs directly tied to getting your sold products ready for a customer.

Another classic slip-up is mishandling shipping and labor costs. So many sellers forget that the cost to ship materials to your warehouse (freight-in) is a direct cost. It absolutely belongs in your COGS. On the flip side, the cost to ship the final product to your customer (freight-out) is a selling expense, not COGS.

The same goes for labor. Only the wages you pay to the people who are physically assembling or making your products count as direct labor. The salaries for your marketing gurus, admin staff, or customer service heroes? Those are all operating expenses.

Here’s how to keep things clean:

A botched COGS figure doesn't just mess with your internal spreadsheets—it directly impacts your taxable income. If you overstate COGS, you could end up underpaying your taxes and facing serious compliance headaches. Understate it, and you're just giving the government more money than you need to.

Finally, you can create a real financial mess by not sticking to one inventory valuation method, like FIFO or LIFO. Hopping between methods mid-year without the right accounting adjustments makes it impossible to compare your performance over time. It’s like trying to compare apples and oranges.

Pick the method that makes the most sense for your business, and then stick with it. Every single time. That consistency is the bedrock of trustworthy financial reports and smart, data-backed strategy.

Even after you get the hang of the basics, some specific questions almost always come up when it's time to actually apply the Cost of Goods Sold concept. Let's tackle the most common ones we hear from sellers.

In most cases, no. COGS is all about the cost of making physical stuff.

If your business is service-based—think consultants, graphic designers, or writers—you don't sell tangible products, so you don't really have COGS. Instead, your main costs are tied to delivering that service, and those get recorded differently on your financial statements.

You'll want to run the numbers for every accounting period you report on. For most e-commerce businesses, that means calculating it monthly and quarterly. Then, you'll roll those up for a final annual figure.

Keeping a regular eye on COGS gives you a real-time pulse on your profitability and how efficiently you're producing your goods. It's a health check for your business.

This is a big one, and it's crucial to get it right. COGS only includes the direct costs of producing the items you've actually sold—things like raw materials and the labor needed to assemble the product.

On the other hand, Operating Expenses (OpEx) are the indirect costs you need to pay just to keep the lights on. Think marketing spend, office rent, and administrative salaries.

Keeping these two separate is the key to truly understanding your gross profit versus your net profit. One tells you how profitable your products are, and the other tells you how profitable your entire business is.

Join the Ecom Entrepreneur Community for Vetted 7-9 Figure Ecommerce Founders

Learn MoreYou may also like:

Learn more about our special events!

Check Events